Woodturning Lathe Build Process

Page 64 of 65

Posted 18th January 2026

I've mentioned a couple of times that one of the remaining jobs on the lathe was to make the little cover flap that goes over the tommy bar access hole in the front of the headstock. You may also have wondered why I didn't just get on with it and get this ostensibly simple part made.

The truth is that I wanted to use it as an opportunity to try something new and it's taken me until today to figure the process out (having started on the 2nd January). If/when I do it again I'll make some minor tweaks but essentially I think it's repeatable finally.

I think the one I've finished today would probably be the fourth complete attempt, but some of the earlier stages were definitely tried out a lot more times than that. Note that the photos below aren't all from the same disc so don't be surprised if things look a bit different from one to the next!

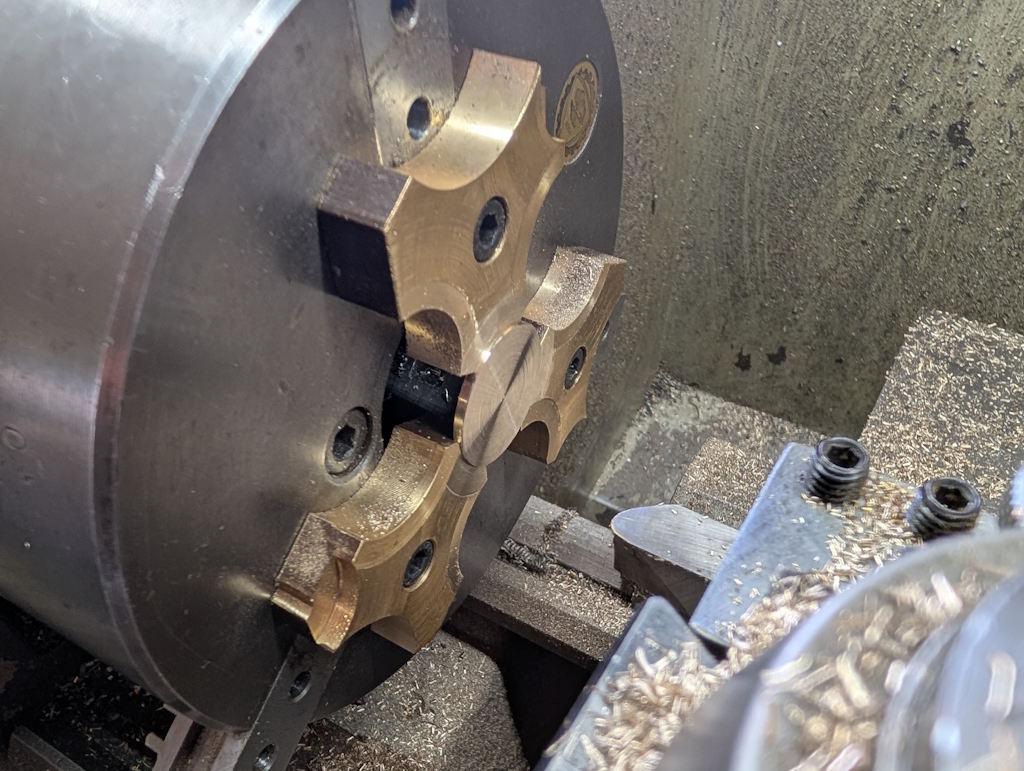

I started with a fairly simple process of taking some 31.75 mm (1¼") brass bar and skimming the outside down to a nice round 30 mm. I then went through a sequence of facing, parting, facing, parting:

That photo was from the first attempt; on later ones I reduced the thickness of the parted off bit. The parted off bits got put back in the lathe using my home-made soft-jaws and each one had its parted face cleaned up with a round-nose tool:

That left me with quite a few discs to play with; this was the set I made for the final round of testing:

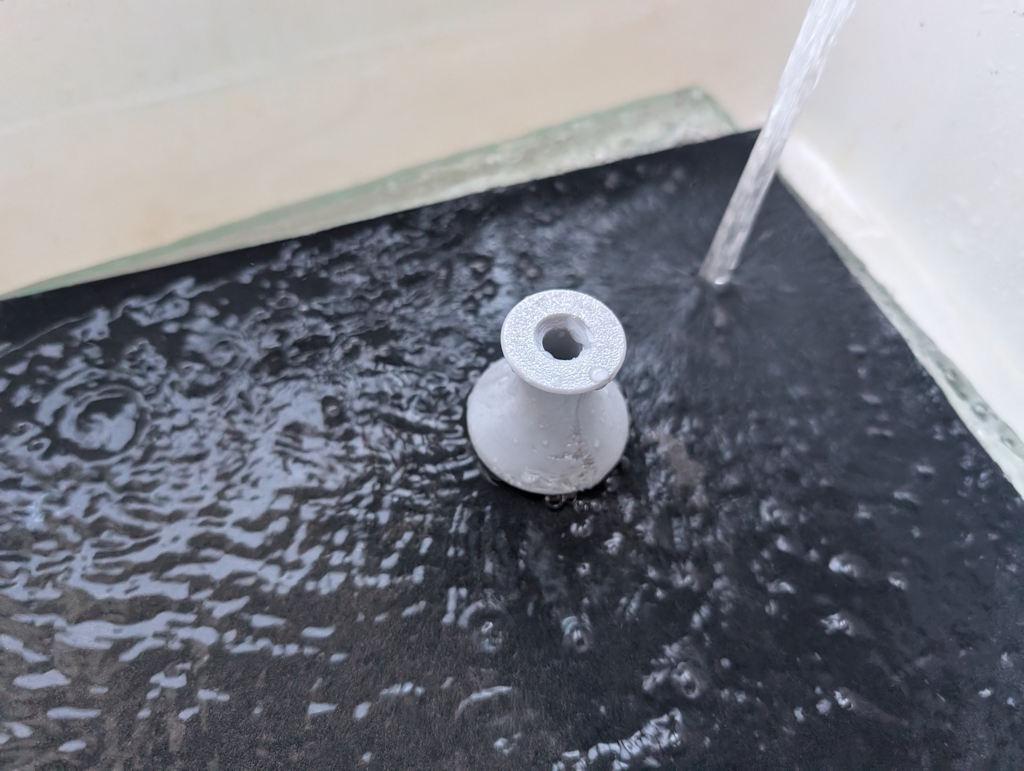

The finish I need for the "show" face needs to be smoother than I can get off the lathe. To help with holding the thin parts, I 3D-printed a little holder with a shallow rim:

That didn't print that well (it was with a reel of filament that had been lying out on the table and probably needed to be dried) but it's good enough. With the discs in the recess in the top face as shown in that image, I flipped them both over and rubbed the disc face on wet-and-dry paper under running water (to make sure no brass swarf accumulates and scratches the surface):

I started at 240 grit (on a 12 mm thick sheet of glass) and followed that with 400 grit and 600 grit. If I do it again I might go up to 1200 grit.

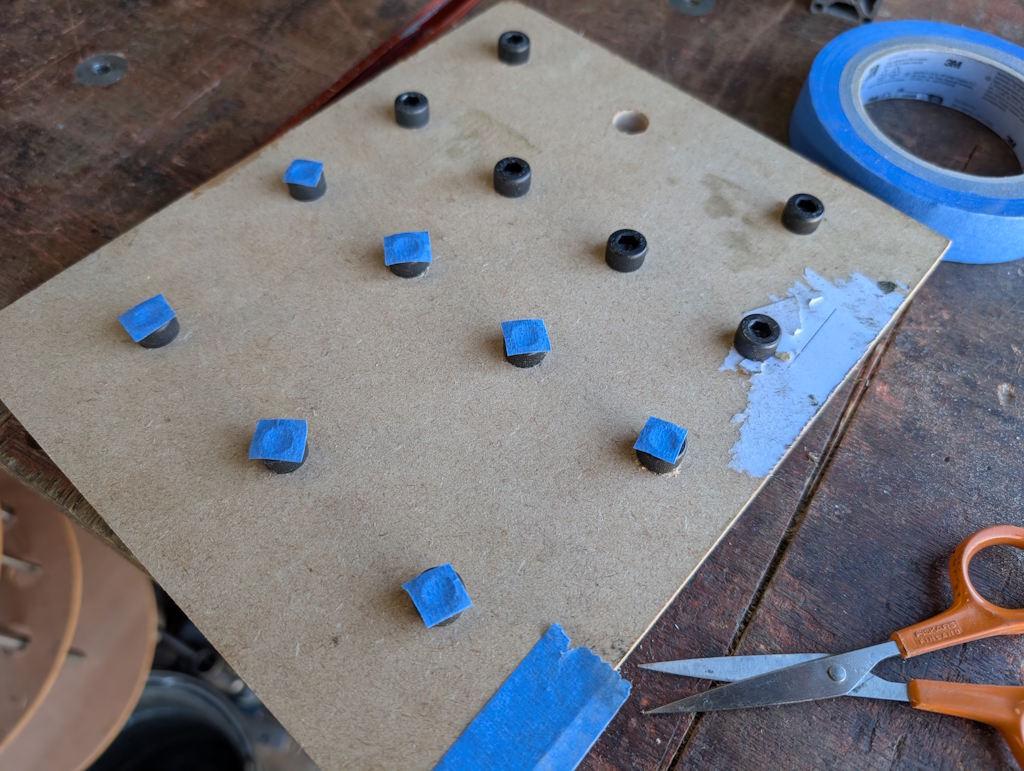

I had a scrappy bit of MDF with some blind holes on one side. I drilled them through about 7.5 mm and tapped them M8 before inserting some short cap screws and covering the caps with masking tape. If I do this again, I'll probably ditch the masking tape:

The discs got placed (sanded face down for the first coat) on the MDF, which was placed on a cardboard base (in the dining room for warmth reasons) and surrounded on three sides with more cardboard. The discs then got four coats (15 minutes apart) of Screwfix black spray paint:

After allowing about 8 hours for the paint to dry, I flipped them over and gave the sanded faces four coats. I later noticed that the masking tape had left a slight residue on the sanded face. It wasn't a big deal in the end, but I think if I do it again I'll paint the show face first and then (carefully) place that on the screw heads (possibly after skimming the screw heads on the lathe to minimise the chance of scratches in the paint).

Here are a batch of 12 discs after the paint had dried:

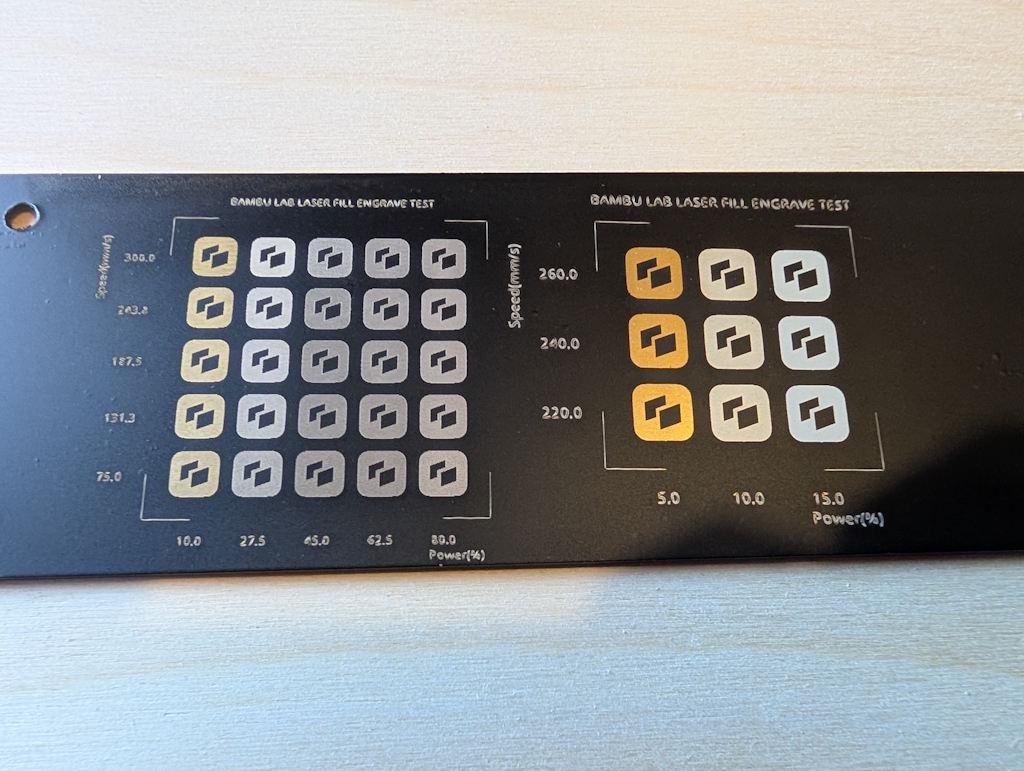

I'd also painted a bit of brass sheet and I used that to calibrate the laser attachment on my 3D-printer:

I did find the laser calibration settings depended (unsurprisingly) on the number of coats of paint, as well as on the thickness of each layer. The conclusion I came to was that increasing the number of passes (i.e. the number of times the laser engraves the image) was a good thing. More passes increases the likelihood of getting rid of all the paint but allows the power to be kept low so that there's less chance of removing paint in the wrong places.

I've found the accuracy of the camera used for alignment of the printer's laser is pretty awful, so I needed a way to deal with that. I started by cutting some 30 mm discs out of 3 mm thick plywood using the laser. I then fitted a sheet of 4 mm plywood and ran the laser job with the pattern I wanted as a laser fill (i.e. engrave) and the outline as a laser cut. That gave me some 30 mm pockets in the 4 mm plywood, into which I dropped the 3 mm thick plywood discs, giving me some 1 mm deep pockets.

The 30 mm diameter painted discs then got dropped into the pockets and the program run again without moving anything (thereby guaranteeing that the laser job would be in the right place). I'd configured the profile such that a "laser cut" on the brass pieces was at minimum power, high speed and with a 2 mm cut off-set. That meant that, after doing the engraving, the laser "cut" program ran in a circle over the plywood (rather than the brass) with so little power that it didn't even mark the plywood, let alone the brass.

That configuration meant that I could use the same program (with laser fill and laser "cut") on the plywood and the painted brass without any alignment worries and without inadvertently removing any paint from the rim of the brass discs.

After laser paint removal, the discs looked like this (I think that photo is from ones that hadn't been sanded before painting, but you get the idea):

I really like the look of the black discs with the brass showing through, but for this application I don't think the paint will last very long, so I need to do more (which is where it gets complicated!)

The next job was to assembly my etching kit:

On the left is a jar of ferric chloride etchant, immersed in a pot of boiling water. It's important to loosen the lid of the jar before doing this: the first time I did it the jar was ejected upwards at high speed!

On the right is a little 3D-printed jig to hold the discs. The tall uprights with the hexagonal holes just hold some sacrificial M10 nuts to weigh it down (on the first version I poured the ferric chloride in and it floated).

The discs get placed face-down in the jig so any removed brass can fall away and let the etchant keep working:

It then gets drowned in the warm ferric chloride and I poured another kettle-ful of boiling water into the surrounding dish to help keep it warm:

About six or so sheets of cardboard and then a couple of tea towels were piled on top to help insulate it but that didn't seem worth a photo!

One of the main process variables here is how long it spends in the etchant. After trying quite a few options I settled on a 90 minute etch. Every 30 minutes I took the cardboard "lid" off and gave the jig a little wiggle to shift any stuff that the etchant had removed but had stayed in place.

Out of the etchant, it looks a bit like this:

Acetone removes the paint:

The dot at the top got centre marked and then drilled 2.1 mm. Heat is then applied with a blowtorch:

Dial wax (black shellac) is then applied, melting into the etched grooves (note that this one had only been centre marked and not drilled at this point):

It was then back to the kitchen sink for some more sanding. This time I just did it in still water (but still quite a lot of it) as it seems a bit wasteful having the tap running through the whole process.

I started with 400 grit and got it to this stage:

I then used 600 grit for a bit but quite quickly switched to 1200 grit as I didn't want to go too far. The result:

It's a rather matt finish and can be made more glossy, either by sticking in the domestic oven or, as I did, applying some very gentle heat from underneath with a blow-torch:

It's been a lot of work over the last few weekends, but I'm really pleased to have found a process that seems to work. A year or so ago, a very generous member of the MIG-welding forum made some of this sort of thing for me using his CNC engraver. I've still got some of those 20 mm diameter brass discs left but it's much nicer to be able to make them myself as I can customise the size to suit the job in hand (and add features like the dot for carefully aligned drill hole).

When I bought the laser attachment for the 3D printer, I knew it wasn't anywhere near powerful enough to engrave metal directly, but this laser-and-etch process works as a practical alternative that combines the accuracy of the laser with the etch depth of the ferric chloride.

Page 64 of 65

This website is free and ad-free, but costs me money to run. If you'd like to support this site, please consider making a small donation or sending me a message to let me know what you liked or found useful.

Return to main project page

Return to main project page